<< Hide Menu

Dalia Savy

Audrey Damon-Wynne

Dalia Savy

Audrey Damon-Wynne

🎵 Audition

Your sense of hearing is often called audition, but how do we hear sound? It happens when the vibration of sound waves are converted to neural impulses. Each vibration causes molecules to compress and expand; the greater the compression, the higher the amplitude, and the louder the sound.

Another characteristic of a sound wave is frequency, the number of complete wavelengths that pass a certain point in one second. The frequency determines the pitch, which is how high or low a sound is. The shorter the frequency, the higher the pitch. However, even if the same note (pitch) is played on violin and flute at the same volume, you'll notice that they sound different. This is because of the difference in timbre. Sound is measured by the amplitude of the sound waves, with decibel (dB) units.

👂Parts of the Ear

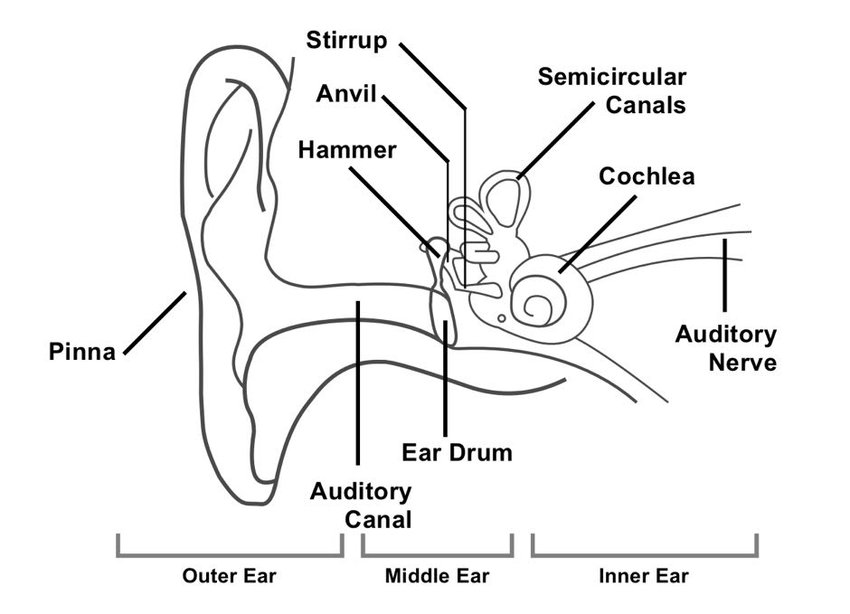

Your outer ear, which is often called the pinna, is where the process begins. The pinna channels the sound wave into the ear canal. Then, a mechanical chain reaction sends the sound waves down through the outer ear to the eardrum. The eardrum is a tight membrane, and when sound waves hit it, it vibrates. Right after hitting the eardrum, three bones in the middle ear (hammer, anvil, stirrup) pick up the vibrations and transmits them to the cochlea.

Image Courtesy of Research Gate.

The cochlea is where the physical stimuli of the sound wave is converted into a neural impulse. Vibrations from the middle ear cause the oval window (cochlea’s membrane) to vibrate, pushing the fluid inside the cochlea. In the cochlea is the basilar membrane lined with hair cells that are bent by vibrations. These hair cells transduce mechanical energy into neural impulses, similar to the process that happens at the retina in the eye.

The hair movement triggers impulses in nearby nerve cells that form the auditory nerve. Similar to the optic nerve, the auditory nerve sends messages to the thalamus, which are sent to the auditory cortex in the temporal lobe.

Note: The inner ear contains the semicircular canals and the vestibular sacs, along with the cochlea. These have to do with your vestibular sense.

🔇 Hearing Impairment

Just like you could lose your sense of sight, you could lose your hearing sense. There are two major types of hearing loss:

- Sensorineural hearing loss, aka nerve deafness, is caused by damage to the cochlea’s cells or damage to the auditory nerve. Therefore, the signal is transferred to the cochlea, but not to the brain. This hearing loss is often caused by heredity, aging, and being exposed to too much noise (rock and/or rap concerts). If someone has nerve deafness, they could have a cochlear implant inserted. This device converts sounds into neural impulses, just like the cochlea would if it functioned properly. This is the only way of restoring the sense of hearing, but it is not very effective in adults.

- Conduction hearing loss is caused by damage to the system that conducts sound waves to the cochlea. This may be damage done to the eardrum or the middle ear bones (anvil, hammer, stirrup). A hearing aid is used for this less common form of hearing loss.

By Matt Ralph - Flickr, CC BY 2.0

🤔 Theories of Pitch Perception

How do we hear different pitches? Two different conclusions were made about this phenomenon:

- The place theory explains how we hear high-pitched sounds. Developed by Georg von Bekesy, it links pitch with the location of the basilar membrane, and it is stimulated because certain hair cells are attuned to certain pitches. Because high-pitched sounds have a high frequency, it will peak near the close end of the basilar membrane. However, low-pitched sounds have a low frequency, its peak will be near the far end. Then, the brain automatically assumes that sounds near the close end are high-pitched while sounds near the far end are lower pitched.

- The frequency theory, also called temporal theory, explains how we hear low-pitched sounds. It suggests that the “rate of neural impulses traveling up the auditory nerve matches the frequency of a tone, thus enabling us to sense its pitch.” (Definition of Frequency Theory). Because an individual neuron can only fire at a maximum of 1,000 times per seconds, but neural cells with alternate firing can achieve a combination of 4,000 firings per second. This, called the volley principle, explains why we can hear low-pitched sounds.

These two theories explain why we hear low and high-pitched tones, but what about mid-tones? The volley principle explains that since neurons cannot fire more than 1000 times in a minute, some neurons alternate firing. These neurons then fire in succession so fast that they create a combined frequency above 1000 waves/second.

Quick note: We measure sound in decibels. 0 decibels = absolute threshold for hearing. A rock band at close range is about 140, a normal conversation is about 60 decibels.

🔊 Localization of Sound

Having two ears, just like having two eyes, is much better than having one. The placement of our two ears on different sides of our head allows us to determine where sounds are coming from. If you are sitting in class and your buddy to your left calls your name, the sound waves of his voice will hit your left ear before the right because it has a bit more distance to travel. That's how we localize sound.

But when the sound is coming from behind you, above you, in front of you, or below you, it is much more difficult to locate a sound. Therefore, tilt your head to help you locate a sound. Doing so gives your ears different intensities of the sound, making it easier to locate the source.

🎥 Watch: AP Psychology - Auditory Sensation and Perception

© 2024 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.