<< Hide Menu

Dalia Savy

Haseung Jun

Audrey Damon-Wynne

Dalia Savy

Haseung Jun

Audrey Damon-Wynne

⚡️Visible Light Spectrum

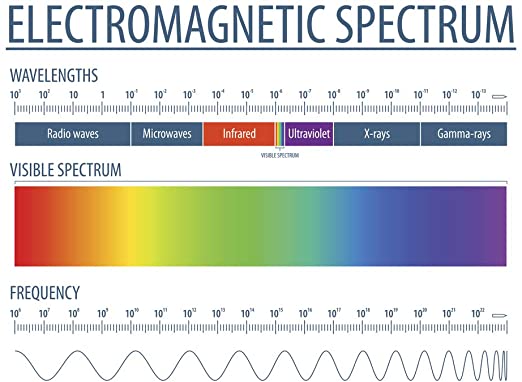

To understand light, you should be familiar with the electromagnetic spectrum. Humans see visible light. The spectrum varies in wavelength from 400nm to 700m, purple to red. Wavelength is the distance between two peaks or two troughs of a wave. Wavelength determines hue, the dimension of color.

Image Courtesy of Amazon.

You should also be familiar with the term intensity, which is the amount of energy in light. For example, if something is really bright, it has a high light intensity; if something is really loud, it has a high sound intensity. Intensity is determined by the amplitude of a wave, which is the wave’s height.

So, what are the other waves on the electromagnetic spectrum? Even though we cannot see these other waves, such as x-rays, other animals could see them. Interestingly enough, bees can see waves from 300-650nm, which means they can’t see the “color” red, but they can see UV rays.

You may wonder why the word color is in quotes. Color is actually a mental construct—objects don’t actually have color. The way that waves reflect an object creates what we perceive as color—our brain gives the object color.

👁 Parts of the Eye

Now we get down to the study of the 5 senses in-depth, beginning with sight!

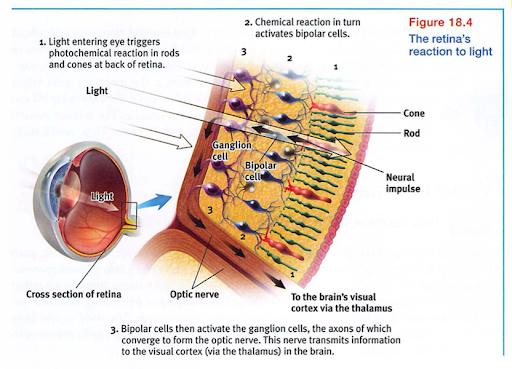

Image Courtesy of Myers AP Psychology Textbook - 2nd Edition

-

First, light passes through the cornea, a thin tissue that protects the eye and bends light to provide focus.

-

Next, light passes through the pupil, a small opening controlled by the iris. The iris is a colored muscle that constricts (gets smaller) or dilates (gets larger) based on light intensity. The more light exposure, the more the pupil constricts.

-

Behind the pupil is the lens. It focuses incoming light onto the retina as an upside-down image and changes the shape of light. This is called accommodation. The lens is curved and flexible so that it can focus the light. You can feel your muscles changing focus with a classic finger to wall focus. Try folding up your finger 👆 and focusing on it. Then, change your focus and look at the wall. Then change your focus back to the finger. Do you feel it? You should notice that your muscles are working hard to change focus!

-

Once the image is received on the retina, visual information begins to be processed as this is where transduction occurs. Transduction is the process of changing physical energy to neural impulses so that the brain can understand them. The retina contains millions of photoreceptor cells, called rods and cones, that begin this process by triggering chemical changes. Those chemical changes begin a chain reaction in which they first spark neural signals in nearby bipolar cells, which in turn activate ganglion cells—the axons of which converge to form the optic nerve which sends the message on to the thalamus and finally to the visual cortex. This is when we actually "see."

- Rods detect black, white, and gray. There are about 120 million of them in the periphery of the retina. They are more light-sensitive and therefore enable us to see in the dark. They are also necessary for peripheral vision.

- Cones are our color receptors. There are about 6 million of them, clustered in the center of our retina (the fovea). They function best in daylight, and are responsible for helping us to detect fine detail.

**Note: memorizing the differences between rods and cones is essential for this unit! You can easily remember __co__nes are our __co__lor receptors because cones and color both start with the letters c-o. **

-

In the visual cortex, cells that respond to specific features of a stimulus are found. These are called feature detectors (discussed in more detail below).

-

Where the optic nerve leaves the eye is a blind spot, as a result of the absence of receptor cells there. The optic nerve is also divided into two parts. The impulse from the left side go to the left hemisphere, while the impulse from the right side go to the right hemisphere. Where the nerves cross each other is called the optic chiasm.

-

If the room becomes suddenly dark, your eyes become gradually sensitive to the low-light environment. Have you been able to sense moving things even in the dark? It might be due to your eye's dark adaptation, which is a result of shifting from cone vision to rod vision.

Image Courtesy of Myers' AP Psychology Textbook - 2nd Edition

As mentioned before, feature detectors were discovered by Hubel and Wiesel in the visual cortex. They pass information about stimuli (lines, angles, edges, and movements) to other regions of the brain where supercell clusters (a team of cells) work to respond to the patterns. Supercell clusters are so specific that researchers looking at fMRI scans can tell exactly what someone is looking at.

Since every stimulus has a million lines, shapes, and edges, how does our brain process all of this at once? Through parallel processing, we are able to divide a visual scene by these aspects and work on each aspect simultaneously.

🌈 Theories of Color Vision

Remember the electromagnetic spectrum? We only see visible light, which corresponds to ROYGBIV. The longest wavelength corresponds to red and the shortest corresponds to purple. But how do we really see color?

Thomas Young and Hermann von Helmholtz came up with a theory that the retina contains three different color receptors, hence RBG (red, blue, green). This theory is called the Young-Helmholtz Trichromatic Theory, and they concluded that these three colors combine to produce the other colors we see.

People who are colorblind may lack one or two of these color receptors. Their vision may be monochromatic (one color; lacking two receptors) or dichromatic (two colors; lacking one receptor). Men are more likely to be color blind than women.

Another psychologist, Ewald Hering, came up with the Opponent-Process Theory. The basic idea is that color vision depends on three sets of opposing retinal processes: red-green, blue-yellow and white-black. As the neural impulse travels to our visual cortex, some neurons are turned on by red and off by green; others are turned on by green and off by red. The same is true for the blue-yellow and white-black "opponents." This theory can be demonstrated by the flag afterimage demonstration below. Stare at the center of the flag for about a minute, and then look in the white space beside it. What do you see? Theoretically, you will see the opponent colors: red, white and blue. This is because your brain "tires out" the black, green and white neurons and activates the opponent colors.

Image Courtesy of Study

👓 Common Sensory Conditions

Sometimes we need glasses, and maybe one day when you go to the optometrist, they will say you have astigmatism. Here’s what that means:

If you are near-sighted, your vision is blurry when you look at something in the distance (that is, you have trouble seeing things far away but can see near). This is because of too much curvature of the cornea which causes the image in front of you to be clearer than images in the distance. If you are far-sighted, there is too little curvature of the cornea, making the images in the distance seem much clearer (that is, you have trouble seeing things near but can see far).

An astigmatism distorts/blurs the image at the retina. It is caused by an irregularity in the shape of the cornea or lens.

🎥 Watch: AP Psychology - Visual Anatomy and Perception

© 2024 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.