<< Hide Menu

2.8 The Adaptable Brain: Neural Fluidity

4 min read•june 18, 2024

Dalia Savy

Haseung Jun

Megan Revello

Dalia Savy

Haseung Jun

Megan Revello

Vocabulary

| plasticity | neurogenesis |

The Adaptable Brain

One unique trait of our brain involves the idea of plasticity. Plasticity is our brain’s ability to reorganize itself after an accident or tragedy OR modify itself in response to experience/a change. Since the brain is constantly forming new pathways, it can sometimes overcome a stroke or damage and regain skills that had been previously lost through this reorganization.

Our brain's ability to change like this helps account for why the blind have really good hearing senses and the deaf have amazing visual perception. Our minds are much smarter than you think.

If you experience major brain damage, our brain cannot regenerate neurons. Every part of the brain has its own function, so what happens if an essential part of your brain is damaged? Well, other parts of the brain actually help and take over the tasks of the damaged neurons. Your brain🧠 can easily adapt towards any change.

Another way that our brain adapts is through the process of neurogenesis. It is the growth and formation of new neurons, which can grow and form new connections. Neurogenesis, in essence, can heal💖 the brain.

Consciousness

Consciousness💭 is our awareness of ourselves and the environment🌳 There are different states of consciousness: spontaneously, physiologically, and psychologically.

- Spontaneously: Daydreaming, Drowsiness, Dreaming💭

- Physiologically: Hallucinations, Orgasm, Food/Oxygen Deprivation🍔🍕

- Psychologically: Sensory Deprivation, Hypnosis, Meditation🧘 Although you are limited to what you see and are aware of, other events can influence your consciousness. The mere-exposure effect describes our preference in old stimuli (that we've seen before) over new stimuli. For example, a group of participants were given were shown two lists of terms separated by time. However, even if they couldn't remember the words from the first list, they still reported to prefer the first list over the second. Another concept related to consciousness is priming. People tend to respond more quickly and accurately to questions they have already seen even if they don't remember them. Lastly, there is also a phenomenon related to blind sight. People who are blind can still accurately describe the path of an object they cannot see 🤯, demonstrating that a level of consciousness does not involve visual information.

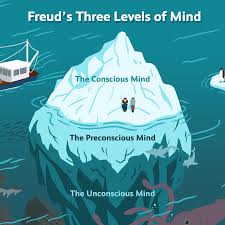

Psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud divided human consciousness into three different awareness levels:

- Your preconscious is out of your awareness, but anything within your preconscious could easily be recalled. For example if somebody asked you what you ate for breakfast🥓🍳 in the morning, you would be able to recall this information and spit it back to them, but it wasn’t in your awareness prior to them asking you about it.

- Your unconscious, according to psychoanalysts, is a level of consciousness that includes all of your “unacceptable” thoughts and feelings, often sexual. You are processing this information unconsciously or without any awareness.

- And your conscious which is everything you see👀, hear👂, touch✋, taste👅, or smell👃

Image Courtesy of Verywell Mind

There are two other levels of consciousness, that describe things not described by the three main levels.

- Your subconscious, which includes information that we are not consciously aware of, yet we know exist because of our behavior. 🤓

- Your nonconscious, or your body processes that you don't control 24/7 (heartbeat , respiration, digestion, etc.)

Cognitive Neuroscience

People who study cognitive neuroscience are interested in the biological processes that create our ability to think, particularly through the various neural connections that exist in the brain.

Another interesting aspect that goes into how we think is our brain’s dual processing capabilities. We can only take in and pay attention to a few things at a time, however, that doesn’t mean we have completely missed the information. Oftentimes information is processed via an unconscious track where we may be able to access it later even though we didn’t consciously attend to it.

Drugs

In key topic 2.5, we went over the three classifications of drugs. Let's quickly go more in depth about the way drugs affect us:

Addiction

With substance use disorder comes addiction. By definition, addiction is the compulsive craving of a drug or behaviors, such as gambling. Although people are aware of the consequences of addiction, it is very difficult to withdraw from substance use.

There are two different types of dependence and addiction: psychological and physiological. Psychological dependence is your desire for the drug, simply saying “I want it,” increasing your tolerance.

Physiological dependence develops when the brain needs the drug in order to avoid withdrawal symptoms. In other words, physiological dependence is the brain’s addiction to the drug.

Tolerance

Tolerance is the diminishing effect of a drug when taking the same dose of it. In order to feel the effect a drug user is aching for, they must take a greater dosage.

For example, you may drink 5 ounces of wine🍷 your first time drinking it and you may get drunk. However, as you continue to drink it, you may need to drink even more🍷🍷🍷 to obtain the same effects because your brain and body get used to the drug.

Withdrawal

So what happens if someone attempts to stop their drug addiction? Unfortunately, it’s very difficult. Since the body is so used to receiving the drug, it doesn’t know how to do without it. Withdrawal is basically the discomfort and distress that occurs if you stop taking a drug.

If your body was physiologically dependent on the drug, it is used to having this certain chemical within it. When the drug acts as a neurotransmitter for so long, the brain might even stop producing that neurotransmitter. Therefore, your body continues to long for the effects of the drug in order to “operate” and without it, there are consequences.

© 2024 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.