<< Hide Menu

9.3 Gibbs Free Energy and Thermodynamic Favorability

5 min read•june 18, 2024

Dylan Black

Dalia Savy

Dylan Black

Dalia Savy

This section of unit nine is all about a concept known as thermodynamic favorability.

Explaining Thermodynamic Favorability

Thermodynamic favorability is used to predict whether a reaction (or any process for that matter, but for our purposes, a chemical reaction) is either spontaneous or nonspontaneous. As we discussed earlier in this unit, a spontaneous process is one that occurs without external inputs, whereas a nonspontaneous reaction requires such external inputs in order to occur.

Spontaneous reactions are considered thermodynamically favorable and non-spontaneous reactions are considered thermodynamically unfavorable.

As we’ll see in section 9.5, spontaneity has intimate connections with the equilibrium constant for the process in question. By measuring a reaction’s spontaneity, we can draw predictions about whether the reaction is product-favored or reactant-favored.

Enthalpy and Entropy

There are two main measures that play into spontaneity:

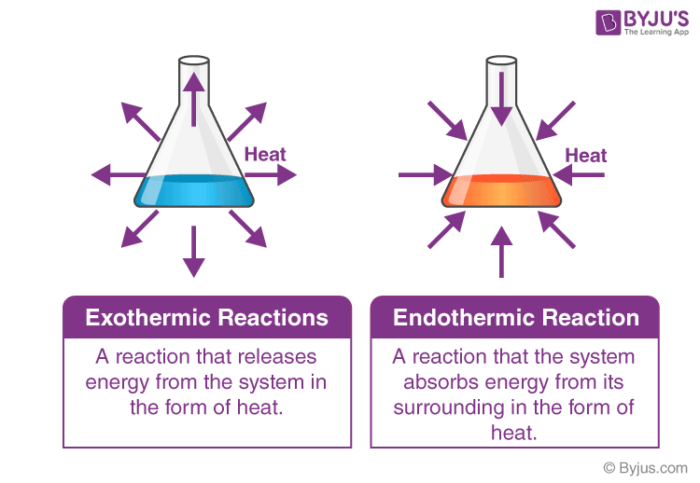

First, we have enthalpy change (ΔH°), the change in the heat of the system relative to the surroundings due to a reaction. If ΔH° is negative, we know our system is losing heat to the surroundings and is thus exothermic. If ΔH° is positive, we know the opposite—the system is gaining heat from the surroundings and is therefore endothermic. Knowing if a reaction is exothermic or endothermic is the first piece of the puzzle.

Image Courtesy of Byju’s

Next, we have entropy change (ΔS°), the change in the disorder in the system. If ΔS° is positive, our entropy is increasing meaning the disorder of our system is also increasing. Conversely, if ΔS° is negative, we are “losing” disorder and gaining order meaning entropy is decreasing. We call reactions that increase entropy exentropic and reactions that decrease entropy endentropic. These terms are pretty uncommon and most likely will not show up on your exam, but they’re nice to know for your future chemistry career.

By looking at the change in enthalpy and the change in entropy as a result of a reaction, we can quantitatively find out whether or not the reaction is spontaneous by introducing a new term: Gibbs Free Energy.

Gibbs Free Energy

Gibbs Free Energy is a new thermodynamic value that is used to determine the spontaneity of a reaction. The formula for Gibbs Free Energy is written in terms of ΔH° and ΔS° along with temperature: ΔG° = ΔH° - TΔS°

The equation for Gibbs Free Energy is given to you during the examination on the AP Chemistry reference sheet.

In simple terms, Gibbs Free Energy calculates the amount of energy available in a system to do work. Therefore, calculating ΔG° tells us the amount of energy either released from a reaction (if it’s negative) or absorbed (positive). From here, we can conclude whether a reaction is exergonic (energy releasing) or endergonic (energy absorbing) and therefore either spontaneous or nonspontaneous.

The formula for ΔG° can be seen as a combination of our two measures of spontaneity. We see enthalpy and entropy combined in one equation meaning both factor into thermodynamic favorability. We’ll see examples of reactions that are endothermic but spontaneous and vice versa because of this reason along with the equivalent statements regarding entropy. The following rules can be applied when calculating ΔG°, but remember to logically understand the rules as well:

- If ΔG° is negative, the reaction is exergonic and therefore spontaneous and thermodynamically favorable.

- If ΔG° is positive, the reaction is endergonic and therefore non-spontaneous and thermodynamically unfavorable.

Practice Problem

Let’s take a look at a practice problem:

Consider the following reaction: 2H2 + N2 ⇌ N2H4. If at 25°C ΔH° = 50.6 kJ/mol and ΔS° = -0.332 kJ/(molK), determine the value of ΔG° for the reaction and conclude whether it is thermodynamically favorable.

In this question, we are asked to apply the formula from above to calculate Gibbs Free Energy change and then use the sign of ΔG° to find the spontaneity of the reaction. Plugging into ΔG° = ΔH° - TΔS°, we find the following:

ΔG° = (50.6) - T(-0.332)

Remember that T has to be in Kelvin, so we can add 273 to 25 to find that T= 298 (this is simply converting from C to K, you should memorize this conversion but it will be on your formula sheet).

Therefore ΔG° = (50.6) - 298(-0.332) = 149.5 kJ/mol.

Because ΔG° is positive, we know that this reaction is nonspontaneous and therefore thermodynamically unfavorable.

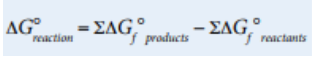

We can also calculate ΔG° similarly to the ways we’ve calculated ΔH° and ΔS°, by using standard free energies of formation for various reactants and products as follows:

Image Courtesy of College Board

Conditions For ΔG To Be Positive or Negative

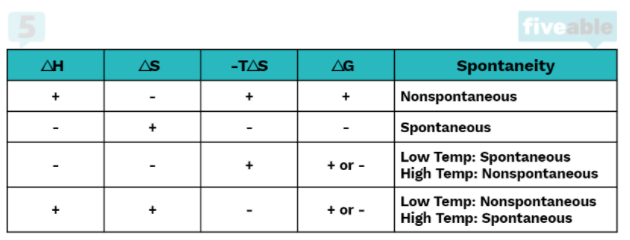

For a reaction to be spontaneous, it must do one of the following: it must be exothermic or increase the entropy of the system. A reaction can have one or more of these qualities and be nonspontaneous, but a reaction that has neither will 100% be nonspontaneous. We can logically see this by looking at the equation for ΔG°: ΔG° = ΔH° - TΔS°

In order for a reaction to be spontaneous, ΔG° must be less than zero. If a reaction is both endothermic (ΔH° > 0) and decreases entropy (ΔS° < 0) there is no chance of this happening because a positive minus a negative will always be positive.

However, if one of the two is true, the reaction could be spontaneous or nonspontaneous depending on the temperature. If the reaction is exothermic (ΔH° < 0) but does not increase entropy (ΔS° < 0), it will be spontaneous at low temperatures. This is because at high temperatures -TΔS° (which in this case is a positive number) will overtake ΔH° and cause ΔG° to be positive.

Conversely, if the reaction is endothermic (ΔH° > 0) but increases entropy (ΔS° > 0), it will be spontaneous at high temperatures because -TΔS° must be large enough to overtake the positive ΔH° to make ΔG° negative.

Finally, if both conditions are met, that is if ΔH° < 0 and ΔS° > 0, ΔG° will always be negative regardless of temperature. This is because a negative minus a negative will always be negative.

The following chart shows these rules more neatly:

Entropy and Enthalpy-Driven Reactions

These rules help us predict how a reaction will act without going through the calculations of ΔG°. It also may enable us to predict whether a reaction is entropy-driven or enthalpy driven.

For a spontaneous reaction, we call it entropy-driven if the spontaneity is mainly driven by an increase in disorder. For example, the dissolution of NaCl is a spontaneous process but is endothermic. Therefore, the spontaneity must be driven by the entropy increase from the dissolution of NaCl(s) into Na+ (aq) and Cl- (aq).

The opposite can be said for an enthalpy-driven reaction. This is a reaction that shows a decrease in disorder but is exothermic.

© 2024 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.